So, in my last post, I asked you to ponder the following question:

- How many tons do you have when you put two 14-ton dump trucks on the same scale?

Now, because of my stunning prescience, I already know your answer:

“Wait…a question? What question? THAT question?!? You thought

I’d actually ponder some question? Bahahahahahahaha…[passes out]”

Now that you’re back…

…let’s actually address this question.

Sooooo…(14 tons) + (14 tons) = 28 tons. Easy enough, right? Right?

Well, first, what is meant by “14-ton dump truck?”* Do you really think that it is exactly (14 tons) × (2000 pounds/ton) = exactly 28,000 pounds? Do you really think that two of them give exactly 56,000 pounds? As in exactly 56,000.000000000000000000 pounds?

*To make sure that we’re not just playing games, let’s assume that these trucks are empty, and we won’t be putting anything into the dump bed.

Sure, that’s the pure calculation of “14 × 2000 = 28,000” and of “2 × 28,000 = 56,000,” but exactly 56,000.000000000000000000 pounds? Oh, c’mon now. That 18th decimal place is so small and so sensitive to change that the impossibly small amount of rust that accumulated (or the impossibly small amount of paint that flaked off in the gentle breeze) while you were reading this sentence changed that value somewhat.

Vehicle weights are typically rounded off to the nearest ton. Consequently, a “14-ton” truck could really be anywhere between 27,000 and 29,000 pounds.*

*As a personal example, my family owns two Nissan Pathfinders. My wife drives the considerably newer one, and it is considered a 2-ton vehicle. “So it weighs 4,000.0000000000 pounds?” Uh, no. It’s a “chubby” two tons, coming in around 4,300 pounds.

What would happen if both of those dump trucks were, say, 28,600 pounds. By using conventional terminology, these trucks would both be classified as “14-ton” trucks.

But their combined weight would be 28,600 + 28,600 = 57,400 pounds. Now, 57,400 pounds is closer to 58,000 pounds (29 tons) than it is to 56,000 pounds (28 tons).

Thus, we have an example here of (14 tons) + (14 tons) = 29 tons.

“14 + 14 = 29? That’s heresy!” Well, yes. Uh…I mean, no… Uh…I mean, yes, “14 + 14 = 29”; but, no, it’s not heresy. I’m afraid you’ll just need to look for another witch (I guess I’d actually be a warlock in this case.) to burn.

But recall all of this in the context of the previous post:

- In the context of the integers under normal arithmetic, 2 + 2 is certainly 4.

- Similarly here, in the context of the integers under normal arithmetic, 14 + 14 is certainly 28.

- In the context of addition modulus 3, 2 + 2 is certainly 1.

- Similarly here in the context of addition modulus, say, 20, then 14 + 14 is certainly 8. [Without rehashing all of the last post, this calculation is 14 + 14 = 28 (“too big!”). Subtracting 20 gives 28 – 20 = 8.]

- In the context of adding water and alcohol, 2 + 2 is certainly 3.84 (within rounding)

- In the context of adding water and (a LOT of) alcohol, 14 + 14 is certainly 26.88.

But now we add a new context entirely:

- In the context of approximation,

(approximately 14) + (approximately 14) could possibly be (approximately 29).- Consider the 28,600-pound trucks in the original example.

- Of course, we could also have

(approximately 14) + (approximately 14) could possibly be (approximately 28).- Consider one truck being about 27,800 pounds and the other being about 28,500 pounds, giving 56,300 total pounds.

- Or finally, we could have

(approximately 14) + (approximately 14) could possibly be (approximately 27).- Consider two trucks being about 27,400 pounds each, giving 54,800 pounds total.

There’s a joke among mathematicians* that “Two plus two equals five (for large values of two).”

*Yes, those exist. That is, I mean “jokes among mathematicians”–not “mathematicians.”**

**Wait, I mean, yes, mathematicians also exist. It’s just that I meant…uh…[head…hurts…SO…BAD……]

Well, considering the above scenarios, it’s quite possible that two “2-pound” objects could technically weigh approximately 2.35 pounds each (“large values of 2” in the joke). Their combined weight would be 4.7 pounds, rounding off to 5 pounds.

Now, I can anticipate an objection: “If we know they’re 2.35 pounds each, why don’t we just say so and have a total of 4.7 pounds? That way, we don’t have to resort to rounding (and your subsequent mathematical witchcraft…)”

I would certainly agree with that. But–leaving aside our unhealthy excitement over decimal places–consider that sometimes we do not know that they’re 2.35 pounds each. We often do not know that the combined weight is 4.7 pounds. We often cannot know such information.

Why not? Well, simply put, you need a scale that can measure to that level of accuracy.

Let me concede that this isn’t necessarily a problem when measuring things around 4-5 pounds. Grocery scales, for example, often measure to the fraction of an ounce. If you were to rummage around my house, you would find a simple home scale* that measures to the gram (approximately 1/28 of an ounce).

*And I would invite you to do so as well. I haven’t been able to find that thing for ages.

But, what a lot of people do not comprehend is that even these “precise” values are rounded off, too.

It’s not that hard to understand that, if a scale only displays the nearest pound, then anything between 4.5 and 5.5 pounds will round off to “5” on the display.* This is more likely to been seen on a bathroom scale that shows a weight of 153.** In this instance, the displayed “153” could be anything between 152.5 and 153.5.

*”But I learned in school that 5.5 rounds up to 6?” You’re not wrong, but I’ll get to why that doesn’t ever really come into play here.

**My personal experience considers a weight of 153 to be purely theoretical.

But a scale that displays an extra decimal is also rounding off as well. For instance, the bathroom scale at my home might display 153.2 (again, purely theoretical). Here, the displayed “153.2” could be anything between 153.15 and 153.25.

Well, if precision matters, why not just add another decimal place?

Or another?

Or…another?

When does it stop?

Unfortunately, it never stops. And when it comes to things that are measured (such as weight or height), we can only ever know things within a certain range of values.* Even a scale that measures something as precisely as “153.18720043”** is just rounding off an actual value that is somewhere between 153.187200425 and 153.187200435.

*And that’s why theoretically we don’t worry about rounding, say, 5.5 up to 6. Nothing measured is ever exactly 5.5 anyway. It’s always a little bit more or a little bit less than 5.5.

**And something that can measure that accurately would be fantastically expensive.

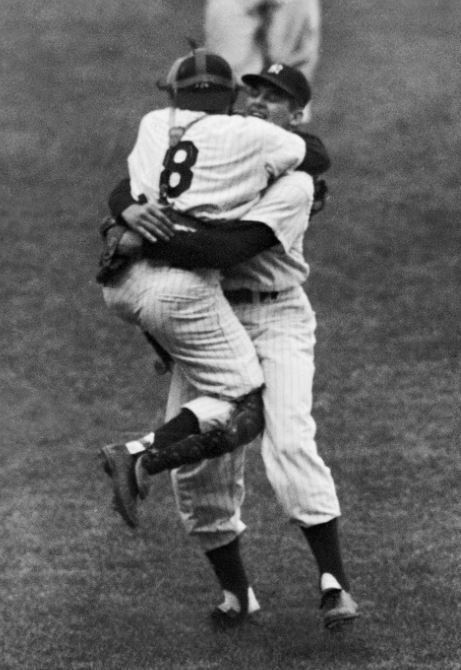

There is a massive difference between things that can be measured and things that can be counted. I can know with absolute certainty that, having counted them, there are exactly 70 mugs in my office right now.*

*That is not an exaggeration, and that only counts the ones that I can actually use to drink my (obscene amounts of) coffee.

What I cannot know with absolute certainty is the exact volume of any of them. Does my “Happy Narwhal” mug* hold 15 fluid ounces? or 15.2? or 15.18? or 15.183? or 15.1831? or… I hope by now that you get the point.

*Thanks, kids! I know it’s actually my “Hypodermic Narwhal” mug, but there’s just not time for an explanation here. Besides, this blog is ultimately for you, and you already know the meaning behind “Hypodermic Narwhal.”

And this is where the uncertainty creeps in. Not in the actual calculation, per se, but in the numbers that can be put into that calculation in the first place.

Without belaboring the point (for now*), the term for measurable things is continuous, and the term for counted things is discrete.

*After all, I can’t help but belabor points. I’m just going to do that…uh…’belaboring’ in the next post.

The mathematics of counting values is pretty straightforward [i.e., (70 current mugs) + (15 new mugs from my rabid fan base) = (85 total mugs)]. The mathematics of measured values, however, is a lot trickier. For example, pouring about 12 ounces of coffee out of a carafe that holds about 60 ounces leaves about 48 ounces in the carafe.

But what if it’s a “small value of 12 ounces” and a “large value of 60 ounces”? What does that say about the remaining “48 ounces”?

If that sounds like an overly-complicated way to think about this situation, I’d wholeheartedly agree. After all, who really cares about the precision of pouring a cup of coffee? Especially if I’m just doing so at home or the office, why would I care about 11.7 versus 11.8 ounces?

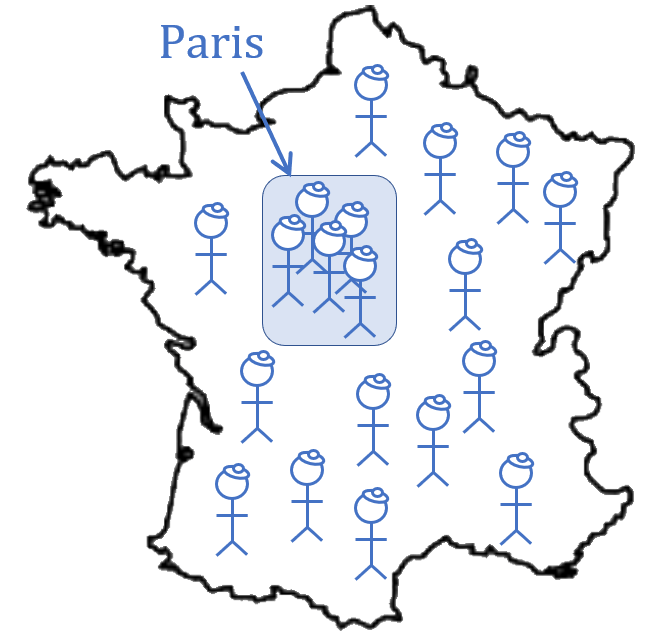

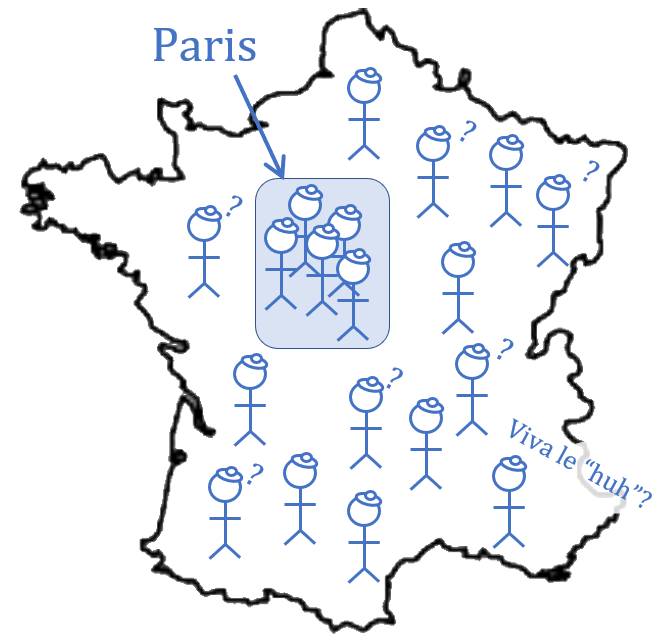

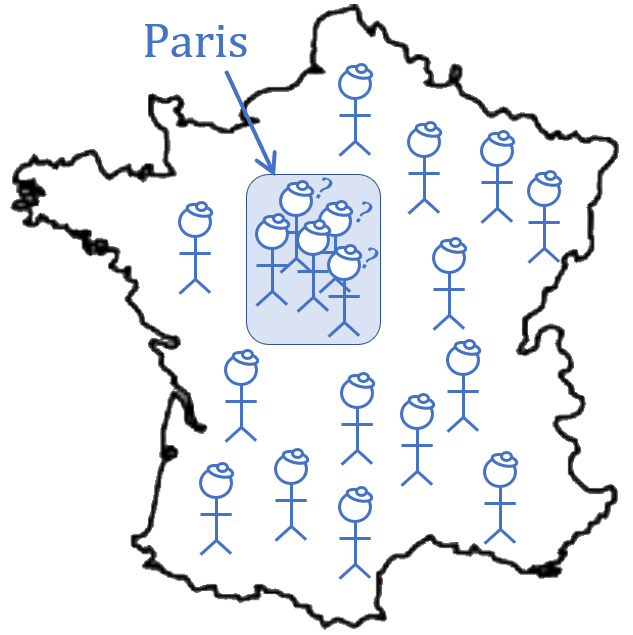

But where it matters is if we know that approximately 48% of voters will vote one way and approximately 47% vote the other. This is especially because “48%” in these contexts does not mean “between 47.5% and 48.5%” but rather “between 45% and 51%.” And, similarly, “47%” means “between “44% and 50%.”

There’s a lot of overlap in those ranges, and a “small value of 48%” combined with a “large value of 47%” can lead to an immensely different political landscape than the original “48% v. 47%” would imply.

What fun…