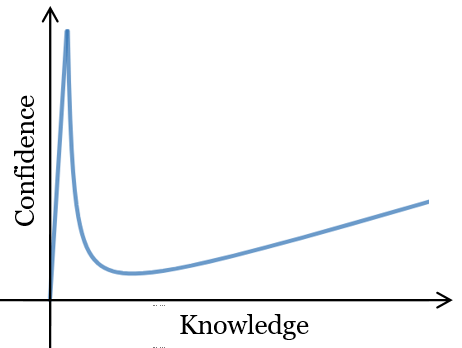

So let’s finally finish this discussion of the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

Last week we looked at the slow and steady rise in the justified confidence someone develops as that someone slowly and steadily masters some discipline.

But let’s finish by looking at that initial spike.

If you think about it, this spike provides a good self-check on where one lies along the knowledge spectrum. How so? Well, if you’ve never had that soul-crushing drop that follows the spike, you’re likely on the very low end of the knowledge spectrum.

Let me give two examples from my own personal experience.

The first comes to my mind because of a conversation I recently had at lunch. The (thoroughly mind-numbing) topic was designing a survey questionnaire.

Now imagine that you were supposed to design some survey about any topic…say, the quality of the major news media outlets. Would you have said, in the words of the immortal Jeremy Clarkson,* “How hard could it be?”

*the most juvenile host out of the three fantastically juvenile (in other words…brilliant) hosts of the British Top Gear hosts–that is, the only real Top Gear

The novice quickly throws together some questions that on the surface appear to address the issue. Problem done!

If you’ve ever studied survey design (and, as part of some early graduate work, I was once stuck doing that very thing), you’ll quickly know that there are at least a half-dozen stages of properly designing a valid and reliable* survey. And several of these steps occur long before even writing a single question.

*By the time I finally give up on this blog, we will all be tired of these two terms. Why? They are everywhere when it comes to proper research designs. But, for now, don’t worry about what their specific meanings in the context of research.

“Aww…come on! You’re making it out to be harder than it really is!”

Anyone who uses that sentence, my friend, means that that person is stuck on the top of the spike: supremely confident but also supremely ignorant.

Consider even something as “simple” as asking about who people will vote for in some election. Consider–as an admittedly abridged example–that we tend to lump all candidates into the Republican or Democrat camps. There is a mammoth difference between the following two questions:

- Do you plan to vote for the Democratic candidate or for the Republican candidate in the upcoming election?

- Do you plan to vote for [insert the Democratic candidate’s actual name here] or for [Republican’s name] in the upcoming election?

Sure, there will likely be some overlap in the results of the two questions, but with a very partisan electorate, that overlap can make all of the difference.

The point here is not survey design (though it may come up at some point). The point is how you responded to the seemingly “simple” notion of designing a survey:

- The novice says, “How hard could it be?” out of sheer ignorance.

- The practiced amateur (such as a graduate student) says, “It’s really hard.”

- The seasoned professional says, “It is a hard task, but I’ve done it enough times that I think I’ve got a good handle on it.”

The problem is that we give the first answer while we think we’re giving the third one.

And THAT is where “soul-crushing doubt” serves as the proper self-check: If you have never had that soul-crushing doubt, then you have never moved past that spike of ignorant confidence.

And, you know…I originally planned to discuss two personal examples, but I think the one will suffice for now. Besides that other example is going to pop up indirectly time and time again over the next several weeks and months.

So…two good pieces of news!

- short blog post this week!

- done talking about Dunning-Kruger Effect!

Next week we will get a bit philosophical. But I’ll write about that next week. And–because I told you it will be philosophical–I suppose I’ll see you again in a few weeks…