After spending far too long talking about being aware of how much we actually know about some topic, I am prepared to somehow get even more boring. It’s a gift, actually, to take something that is already mind-numbing and make it completely mind-deadening.

But the fact that you have pressed on and are now reading this sentence indicates* that you have a suitably dead soul, and we can press on. But don’t say you weren’t warned. This post is going to be packed full of Grade-A Boring. But I’m afraid that it’s all necessary for understanding the next few weeks’ posts.

*When first typing this sentence, I accidentally typed indicts. That might actually be a better description of the kind of person who reads/writes this stuff.

So…ask yourself the following:

How do we know anything at all in the first place?

I warned you at the end of my last post that this one was going to get philosophical, and few questions–if any–have gripped the minds of philosophers more than this one.

Naturally, the first thing a philosopher does is come up with a Big Name to describe this topic. This does two things:

- It makes the the philosopher sound knowledgeable: the bigger the name, the bigger the brain.

- It delays the need to actually answer the question. The effect is basically this: “I, [insert suitably ostentatious Greek name here] have founded the study of [insert newly-invented–but still suitably ostentatious–philosophical name here] and will be forever connected to this philosophical endeavor. It is up to you–the weak–to actually do the thinking.”

The “newly-invented–but still suitably ostentatious” term that some “suitably ostentatious Greek” settled upon was epistemology.

Now, I hate the way new terms are usually introduced: the word is given, followed by the definition. That might be an efficient way to give the information, but it is a horrible way to teach the information. Whenever I introduce a new term in my classes, the first thing I usually do is break down the work into its component parts.

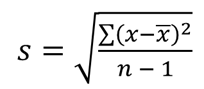

One common example from my statistics classes is the term standard deviation. I usually give the term and then ask the students what is means. Of course, they look at me like I’m stupid (they’re not entirely wrong there…) because I’m the teacher and they’re the students: how could I expect them to know what the term means before I tell them?

Well, I hope by the time they reach a statistics class they have learned what the word standard means. Obviously, there are several definitions of the term, and I need to guide them to the one that is used in a statistics context. We eventually settle upon the idea that standard means something along the lines of “usual” or “typical.”

I also hope that they know what the word deviate means (while hoping that none of my students are one*)–basically, “to differ.”

*And, yes, I checked deviate v. deviant: https://brians.wsu.edu/2016/05/25/deviant-deviate/.

Thus, before we ever get to the definition of standard deviation, “we” (as if I really gave my students any choice) have settled upon “typical difference” as a basic description. It is then a “simple matter” of talking them through slightly more formal definition*:

*I think it was Malcolm Gladwell who quipped that every equation in a book cuts the number of readers in half. Then I guess I just lost two readers.

But enough of that boring side track as we now we return to our previous boring side track. The word epistemology is effectively two Greek words: episteme (“knowledge”) and logos (“logic; reason”). In other words, epistemology is the study of knowledge.

In particular, epistemology is the topic of our even more previous boring main track, asking this key question:

How do we know anything at all in the first place?

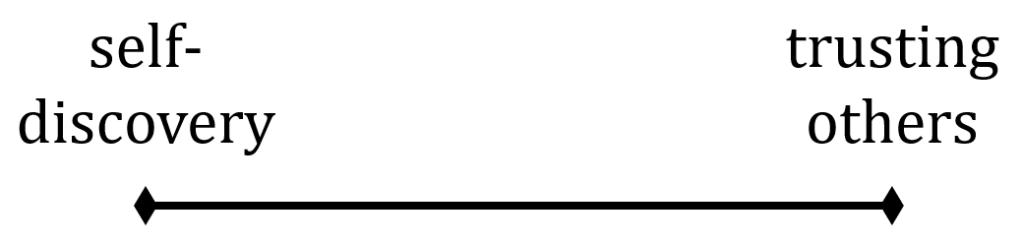

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about how I’d address this because I usually find answers to this expressed along two different scales:

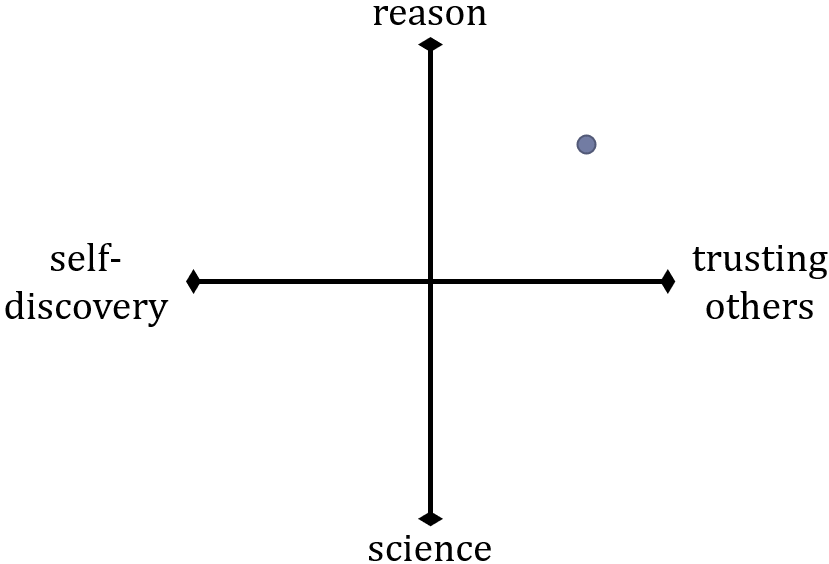

- personal discovery v. absolute trust in others

- pure reason v. scientific method*

*Especially here, I expect to take a lot of grief because a lot of people conflate these two ideas, but I will explain what is meant here over the next few weeks. No…wait…I don’t expect to take much grief at all. Grief can only come from readers. I’m guess I’m pretty safe then.

More times than you can count, I’ve gone back and forth on which these perspectives to use as we go forward in this blog.

Which perspective is the “right” one? They both certainly seem valid.

Which perspective is the “better” one? There are certainly pros and cons to each.

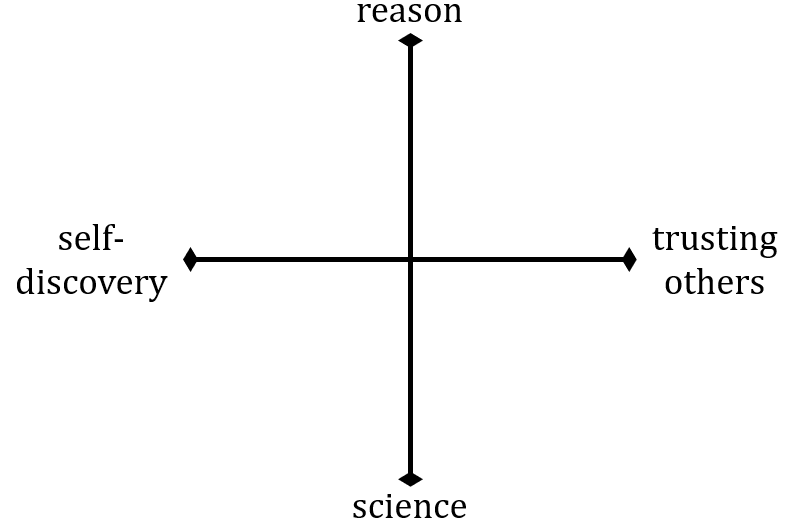

But the more I’ve thought through this problem, the more it became apparent that I couldn’t explain one of the scales without using the other. Perhaps the two scales are complementary rather than competitive.

Thus, I’ve come to believe that these two individual scales actually form a bit of a grid:

I suppose the approach that I’ve been taking for this blog asks the typical reader to be somewhere around here:

Why “leaning towards reason”? Well, I’ve asked you a lot to “think about it,” and then we’ve tried to reason ourselves towards some conclusion. Occasionally, however, I ask you to draw upon your own experiences–the observations that are the root of the scientific method.

Why “leaning towards trusting others”? That one’s pretty obvious: I’m asking you to trust me. But I also expect you to filter everything you read in the context of what you have already learned for yourself.

There’s certainly a biblical basis for this. The Bereans were famously commended in the book of Acts for both listening to Paul and Silas “with all readiness of mind,” but also “search[ing] the scriptures daily” to determine “whether those things were so” (Acts 17:11).

Now, keep in mind that all of this is only to discuss our knowledge of some truth. The truth itself is completely independent from our knowledge of it.

Isaac Newton famously discovered his Universal Law of Gravitation some 300-350 years ago (which has since been refined by Albert Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity), but I have a pretty good feeling that gravity–and the laws governing it–were around long before Newton.

But that’s just speculation…