Judging by the number of views at this blog, it seems like many of you already follow the suggestion of the above title.

But I really want you to ask yourself why you would listen to anything I say–or write, in this particular case–in the first place.

Now, it’s possible that you–for reasons beyond me–believe that I know what I’m talking about, and you come to read this blog in order to learn more.

It’s also possible that you believe that I don’t know what I’m talking about, but you still want to read something that might challenge your thinking. That’s not an unusual position at all; in fact, I find it rather admirable to do that. I find myself often reading things that I do not agree with; I find myself often actively looking for things that I do not agree with.

Why would I–or anyone else, for that matter–do that?

Well, some people are just looking for a fight. And, personally, I just don’t care about those kinds of people. They’re not reading to think; they’re reading to argue. They don’t ever engage in real conversation in that they only listen to others in order to craft a response rather than actually…you know…listening to those others.

Other people–and I’d put myself in this category–look for things that we disagree with specifically because reading those ideas makes me think about what I do believe. After all, how could I identify something is false without having some idea of what is actually true?

For example, as a math teacher, I’ve graded plenty of REALLY bad proofs. But I’ve also graded some proofs that were just a bit…”off.” There would be something in the argument that “just didn’t ring right.” It was often frustrating for me–and the student–to state that there was something wrong without knowing exactly what it was. Usually, I’d tell the student to give me a few minutes (or days) to think about it, and each time I was eventually able to pinpoint the error. Knowing and dwelling upon the correct answer gave me enough knowledge to eventually identify the incorrect parts of an incorrect answer.

But all of this has just been a long way to state that some people believe what I have to say, others don’t, and others haven’t really made up their minds yet.

But there’s actually another category of readers: those who realize that I sometimes know what I’m talking about.

And that’s the real catch. If I was always right, things would be easy: do what I say.

If I was always wrong, things would also be pretty easy: do the opposite of what I say. The inimitable Dwight from The Office best encapsulates this approach:

The problem is that I–and everyone else on earth for that matter–have the capacity to be both right and wrong about some idea.

Thus, the key question is not really “Who do you trust?” Let me make this strong claim: Trust is not binary. In other words, you cannot put people into simple “I trust this person” v. “I do not trust this person” categories.

I have a teenage son. You would think that Webster would define teenage son as “person you can not trust.” And there you would be wrong. I actually trust my teenage son quite a bit. For one thing, I absolutely trust him to make the wrong decision about nearly everything.* It is because of that nearly absolute trust that my wife and I have put certain safeguards in our home.

*And I don’t blame him one bit. It is almost the job description of a teenage boy to mess things up.

A much better question than “Who do you trust?” is “In what capacity can I trust someone?”

And by posing that question, I finally finish my 600-word introduction to the next few posts.

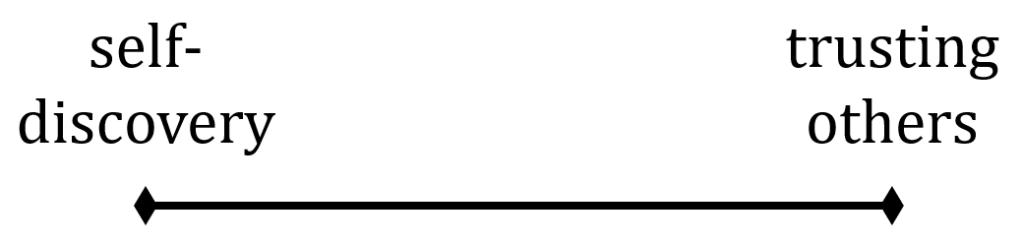

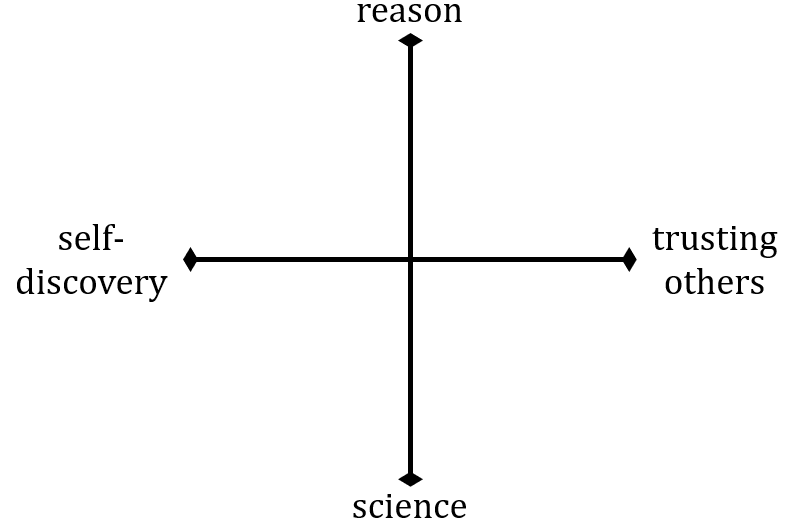

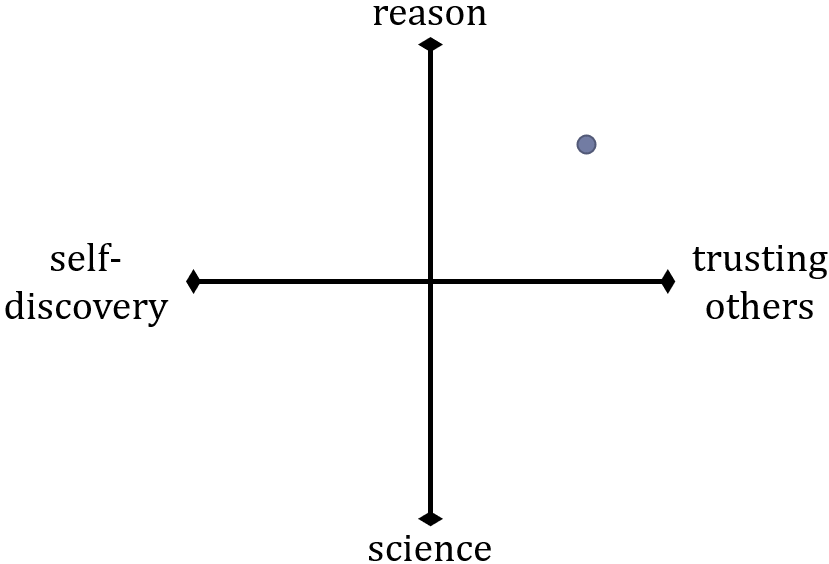

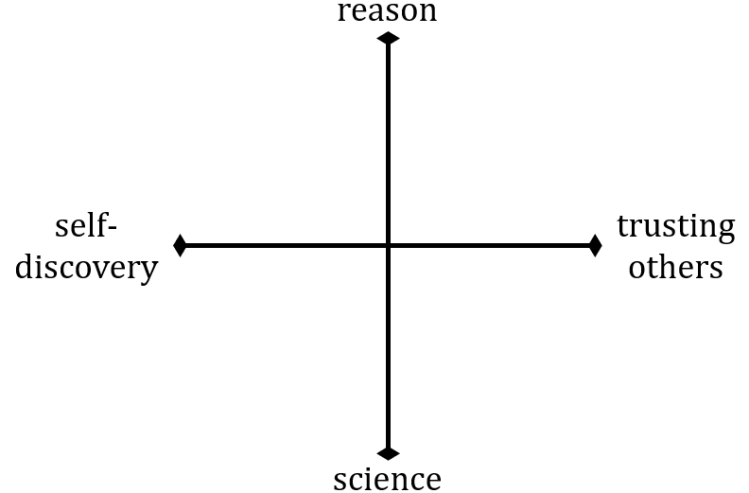

In my last post, I mentioned that there are two complementary scales that help us identify how we know something:

Starting with this post,* I want to examine first that horizontal scale: learning through self-discovery v. learning through our trust in others.

*And considering I’ve already burned nearly 650 words so far, I don’t expect to actually get very far this week.

And with that, let me go all the way back to the title of this post: Don’t Listen to Me. Well, you’ve made it this far, so you either (a) are terrible at instructions or (b) are expecting that the title was some sort of set-up. And, yes, it was some sort of set-up.

It is true that I do NOT want you to listen to me…about certain things…about many things…in fact, about most things.

Suppose you were to pick any topic at random. Well…you’re welcome because I just did. I googled “word of the day” and Merriam-Webster brought up the word encumber. I know what that word means, but–to be honest–the word encumber isn’t really that big of a topic. However, one of the definitions mentioned “to burden with a legal claim (such as a mortgage).” BINGO! Let’s talk about mortgages! (And that “whooshing” sound you hear now is my last reader leaving the site…)

I’ve had to go through the whole mortgage process before, signing 35 pages of the tiniest print imaginable. But I can’t say that I’m an expert on mortgages.

I’ve taught compound interest calculations in my mathematics classes before. But I can’t say that I’m an expert on mortgages.

I’ve even had the…privilege?…opportunity?…trauma?…of teaching how mortgage payments are calculated and how exactly pre-payments can cut time off of the payment schedule. BUT I CAN’T SAY THAT I’M AN EXPERT ON MORTGAGES.

I do know some of the above things, and I like to think that others could trust me on those aspects, but “Mortgages” as a topic is a LOT more than just calculating payments. For example, I don’t know the first thing about situations which would trigger a default and cause the bank to take my home. God–using other family members–has been good to my family, allowing us to always make the payments. And, frankly, I’m thrilled that I am unfamiliar with situations that would trigger a default.

So…long way back to this: Can you trust me when it comes to understanding mortgages? That’s a stupid question.

The better question is this: What things about mortgages can you trust me to know? Calculating a payment is about it.

But even then, you’ve only read my claims about those calculations. That actually takes us to the REAL question: How do you know that you can trust me for calculating a payment?

That’s for next week…